Does enforcement play a role in addressing rough sleeping?

04.04.2017

It is now increasingly well documented just how dangerous and isolating an experience rough sleeping is. It is bad for a person’s health and wellbeing yet sadly the numbers of people sleeping rough are rising across England and Wales.

What we have also learnt at Crisis from our clients is how increasingly those rough sleeping experience enforcement measures that are used to address anti-social behaviour associated with street activity. This in part was the catalyst for Crisis’ new research which explores the impact of the use of enforcement measures on rough sleepers.

The report shows that councils across England and Wales are targeting rough sleepers with measures from the Anti-social behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 such as Criminal Behaviour Orders and Public Space Protection Orders (PSPOs). These tools were never intended to target specific groups such as homeless people or rough sleepers.

The research was conducted over the summer of 2016 and included a survey of over 450 rough sleepers, a survey of local authorities and key informant interviews across three case study areas as well as FOI requests to councils and police forces. The study also recruited peer researchers who all had prior experience of homelessness and were part of the team who conducted face to face surveys with homeless people and contributed a number of photographs of defensive architecture from cities local to them.

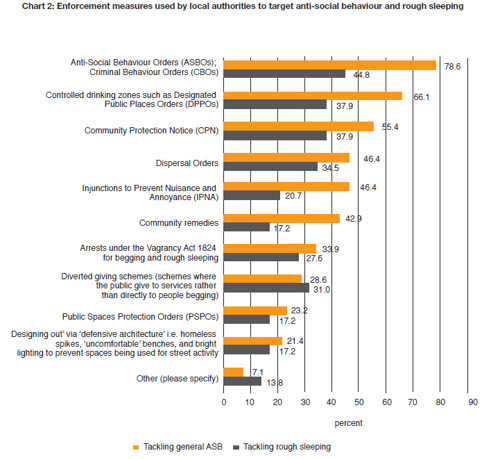

The report reveals the extent of enforcement measures in place. Almost seven out of 10 local authorities make use of enforcement measures to tackle all types of anti-social behaviour which are most commonly formal in nature (i.e. have legal penalties) while more than one in three say they specifically use enforcement to target rough sleeping. The graph below shows this in more detail.

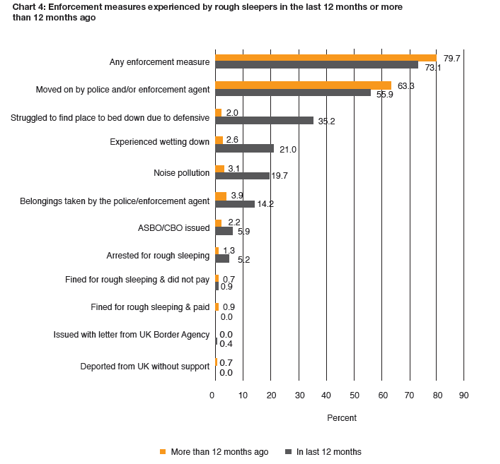

Unsurprisingly, given the widespread use of enforcement by local authorities, nearly three in four rough sleepers had experienced some kind of enforcement in the last 12 months in relation to their rough sleeping.

However, it was experiences of informal enforcement, those not involving legal sanctions, that were far more common than formal measures. The most frequent being that of being moved on by a police officer or enforcement agent – 56 per cent had been moved on in the last 12 months. Thirty-five per cent had struggled to find a place to bed down for the night because of defensive architecture. Peer-researchers’ photos capture how inhospitable our streets are becoming to some of the most vulnerable people in our society. The photo below shows how a bench has been designed to prevent someone from lying down on it, and there were many more examples of public places ‘designing people out’ of areas in the research.

The frequency of contact that rough sleepers have with enforcement agents on the street can be opportunities for positive engagement and while 94 per cent of local authorities said that support and advice always accompanied any enforcement measure taken the experience of rough sleepers told a different story. Eight out of 10 said they received no support or advice during their last experience of enforcement suggesting that informal actions are often poorly supported. These experiences do little to make rough sleepers feel safer on the street nor do they address the shame felt at being homeless.

Rough sleepers’ interactions with police officers, security guards and enforcement agents is also mixed while the actual impact of enforcement measures to change rough sleepers’ behaviour is generally limited, especially in the case of just being moved on. A third said it just made them sleep somewhere else and just over one in 10 became more selective over where they did things.

Any contact with the police, security guards and enforcement agents is an opportunity to provide positive engagement with rough sleepers, build relationships and link them up to meaningful support and accommodation. But the research found that this is being missed in many cases.

While well targeted enforcement with genuinely integrated support can be effective at stopping anti-social behaviour and be a catalyst for helping rough sleepers away from the street if used too early it can be detrimental. Instead it can just geographically displace rough sleepers leaving them marginalised and excluded from much needed support services.

Local authorities indicated that they want to make more use of enforcement measures in the future. In light of this and the report findings, Crisis is calling on local councils to make sure that enforcement measures against rough sleepers are used only as a last resort for genuinely anti-social behaviour and that any rough sleepers affected are offered personalised and accessible support to escape the streets. The government should also reissue its statutory guidance relating to anti-social behaviour powers to make clear that they should not be targeted at rough sleepers or homeless people.

If we are to end rough sleeping we must heed the evidence in this report and ensure enforcement is only ever considered alongside support and accommodation.

Download and read this report.

For media enquiries:

E: media@crisis.org.uk

T: 020 7426 3880

For general enquiries:

E: enquiries@crisis.org.uk

T: 0300 636 1967